Caribbean Reef Shark

(Carcharhinus perezi)

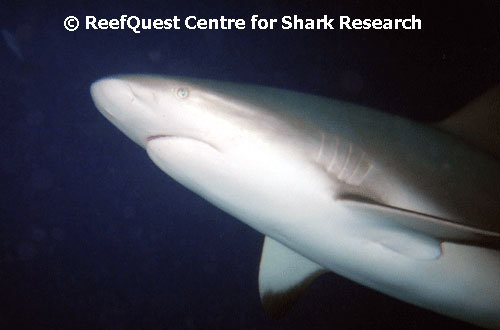

The Caribbean Reef Shark is no stranger to divers of the Florida-Bahamas-Caribbean region. It is one of the most abundant large sharks in the area, especially on outer parts of coral reefs, often participates in organized shark feeds in the Bahamas. As a result, the Caribbean Reef may be one of the most frequently photographed of sharks.

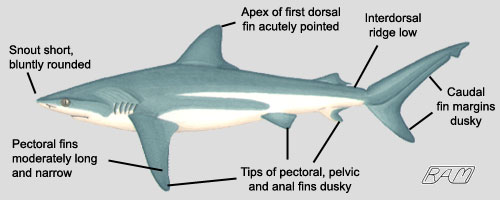

Well photo-documented it may be, but the Caribbean Reef Shark is often mistaken for other species. It can be easily distinguished from Blacktip Sharks (Carcharhinus limbatus), which sometimes mingle with Caribbean Reefs at shark feeds, because Blacktips have a higher and more acutely sloped ‘nape’ (back of the head, above the gill region), distinct black tips on the pectoral fins and lower caudal lobe, and the tip of the anal fin is white. Large, robust individuals are often misidentified as Bull Sharks (Carcharhinus leucas), from which they are most readily distinguished by the Bull’s shorter snout (less than the mouth width) and broader first dorsal fin. The Caribbean Reef Shark is most similar to the Dusky (Carcharhinus obscurus) and Galapagos (Carcharhinus galapagensis) sharks, but divers are unlikely to encounter them within its range. (See the carcharhinid identification page.)

Just the Facts:Size:

Reproduction:

Diet:

Habitat: juveniles in sea grass beds and shallow coastal areas, adults most common on coral reef face and outer reef slopes Depth: surface to at least 100 ft (30 m) Distribution: Western North Atlantic, from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina east to Bermuda (Caribbean) and south to southern Brazil (Amazonian) Danger Rating: ** According to the International Shark Attack File, 22 attacks are attributed to this species, of which 11 were provoked and none were fatal. Remarks: this is the most common large shark of the Florida-Bahamas-Caribbean region and a regular participant in organized shark feeds in the Bahamas. Despite this species’ abundance and the fact that it is fished commercially, astonishingly little is known about its basic life history. |

Caribbean Reef Sharks first attained a kind of fame as the “sleeping sharks” of Isla Mujeres, off the Yucatan Peninsula. They were featured in the April 1975 issue of National Geographic magazine (under the scientific name Carcharhinus springeri), in which Genie Clark investigated how and why these sharks slept in underwater caves. Although it had been known that certain lethargic sharks – such as the Nurse (Ginglymostoma cirratum), Pacific Angel (Squatina californica), and Spotted Wobbegong (Orectolobus maculatus) – could rest motionless on the bottom for extended periods, the Caribbean Reef Shark provided the first evidence of an active shark doing so. Inside the caves, the sharks lay quietly on the bottom, actively respiring 20 to 28 times per minute. Clark discovered that the sharks are not really asleep, but that their eyes follow divers in the cave. Tests revealed freshwater upwellings from the mainland, which may loosen the grip of parasites and perhaps produce a narcotic effect the sharks enjoy. Unfortunately, the famous “sleeping sharks” of Mexico have been pretty much fished out now, victims of that country’s need for marine protein to feed its hungry masses.

Caribbean Reef Sharks are unaggressive toward divers in most contexts. Indeed, those that have been acclimated to the presence of divers by regular organized feedings, seem to regard divers as more-or-less irrelevant, being neither food nor threat. As such, diver-inured Caribbean Reef Sharks often approach quite closely during organized feedings, providing terrific opportunities for photography and videography. But the prudent diver bears in mind that these are large, toothy wild animals capable of inflicting serious injury. During organized shark feeds, you should keep your hands tucked under your armpits or otherwise still and close to your body, as competing sharks may mistake your flashing palms and fingers for a piece of bait and you could very easily be bitten by accident. The Caribbean Reef Shark can become highly stimulated and aggressive when spearfishing is taking place in its presence and the species has been implicated in 11 attacks on divers. None of these attacks were fatal but most – if not all – were probably avoidable.

Although this species does not announce its readiness to attack as blatantly as the Indo-Pacific Grey Reef Shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos), it does signal it is feeling stressed or threatened. If a Caribbean Reef Shark you are watching suddenly switches from serene cruising to short, jerky movements, punctuated by frequent changes in direction and repeated dips of both its pectoral fins: beware. If you are underwater, remain at or near the bottom. Maintain eye contact with the animal and slowly increase the distance between yourself and it. This should result in the shark easing its display or fleeing the scene. The highly stereotyped nature of its display and rapid withdrawal suggest that, under some circumstances, Caribbean Reef Sharks may regard divers as potential predators or competitors.

As with so many aspects of its natural history, little is known about the diet of the Caribbean Reef Shark. It is known to feed on Bigeyes (family Priacanthidae), but – based on its narrow-cusped but finely serrated teeth – probably feeds on a wide variety of other bony fishes as well as rays and large invertebrates, such as octopus and squids. But, as Yogi Berra once put it, “You can see a lot just by looking.”

I once was lucky enough to observe a 6-foot male Caribbean Reef Shark pursue and eat a Yellowtail Snapper (Lutjanus crysurus) in an unbaited dive off Nassau, Bahamas. The shark’s capture technique was fascinating to watch: rather than ‘run down’ the snapper in a flat-out chase, it spiralled and wheeled in a rather languid but focused manner, turning within half its own length to pursue its prey. After several seemingly half-hearted attempts at catching the snapper, the shark accelerated briefly, swung it’s head sharply to the left and caught the fish neatly at the jaw corner. Was this, I wonder, like a boxer who feints with his weaker arm – testing the reactions of his opponent – before delivering the knock-out punch with the other? In any case, such observations of natural predation are rare and I would welcome first-hand accounts from readers.

In recent years, organized shark feeds have provoked considerable controversy. Critics claim that this activity changes the behavior of sharks and the structure of reef ecosystems. There is concern that sharks become dependent on these ‘hand outs’ and may associate all humans with food, increasing the likelihood of attack. Proponents argue that sharks are simply opportunistic, if the feedings stopped, the sharks would simply disperse and go back to feeding upon whatever they fed on before. Although accidental nips have occurred (mostly received by ‘shark wranglers’ conducting the feed underwater), there is no good evidence that shark feedings increase the likelihood of attack away from the feeding site. The issue of modifying reef ecosystems is more difficult to assess. Yes, shark feeds may concentrate predators artificially and the intensified removal of fishes from the environment for use as shark bait is a concern. But populations of sharks and other reef predators have been seriously depleted by overfishing and habitat erosion and many operators use left-over scraps from local restaurants, using fish remains that otherwise would have gone to waste. Clearly, this is a complex issue and a quick or easy resolution is not on the horizon.

In my opinion, responsibly conducted shark feeds – complete with a good shark biology and conservation message – are spectacular, educational, and reasonably safe. Many divers who are already admire and are fascinated by sharks enjoy the opportunity to observe and photograph them from close range. Divers who fear sharks due to ignorance and inexperience come away from organized shark feeds with a new-found respect and appreciation for these marvelous creatures. Not only are they delighted they were not eaten, but they are invariably in awe of their graceful lines and swimming movements. As the most frequent ‘dinner guest’ at organized shark feeds in the Florida-Bahamas-Caribbean region, the Caribbean Reef Shark is a sleek, beautiful ambassador to sharkdom.