Deep Sea: the Twilight Zone and Beyond

Megamouth Shark

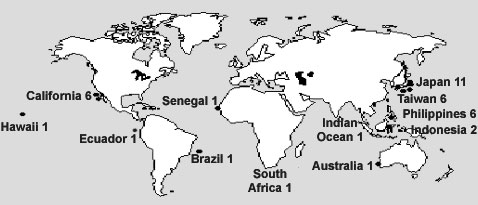

First captured off Oahu, Hawaii, in November 1976 and now known from only 14 specimens from scattered locations around the globe, the Megamouth Shark (Megachasma pelagios) is one of the most spectacular ichthyological discoveries of the 20th Century.

Just the Facts:

Size:

Reproduction:

Diet:

Habitat: Open Ocean, Deep Sea Depth: 40-545 ft (12-166 m), possibly to 3,300 ft (1,000 m) Distribution: Central Pacific, Tropical Eastern Pacific, Amazonian, West African, South East Asian, Western Australian, Japanese |

Named for its huge, bathtub-sized jaws and rubbery lips, Megamouth is highly unusual among deep-sea sharks in that it is apparently a filter-feeder. Along the inner lining of its gills are rows of cartilage-cored, finger-like gill rakers, which the animal almost certainly uses to strain food from the surrounding seawater. Known prey of the Megamouth Shark consists entirely of planktonic animals, including euphausiid shrimps, copepods, and the Pancake Jellyfish (Atolla vanhoeffeni). Yet most plankton is found near the surface, so it is something of a mystery how Megamouth manages to find enough to eat.

Megamouth gill rakers

Because the Megamouth Shark’s upper jaw features great sheets of silvery, reflective tissue, it has been speculated that its lower jaw might be bioluminescent and the creature may use living light to draw planktonic prey to itself. Had this been true, Megamouth would have been by far the largest known bioluminescent organism. Unfortunately, histological examination of its lower jaw tissues revealed no light-producing organs — another beautiful theory slain by an ugly fact.

Examination of Megamouth’s anatomy has revealed that its jaws are highly protrusible and its basihyal (‘tongue’) is large and unusually mobile. In theory, coordinated jaw protrusion and basihyal flexure could significantly expand the volume inside Megamouth’s throat, creating a partial vacuum to help suck in planktonic prey. While this makes good intuitive sense, confirmation or refutation of this scenario will have to await documentation via film footage of a Megamouth feeding in the wild. As well established as is the field of comparative anatomy, there is only so much one can learn from a lifeless specimen.

In October 1990, scientists had a rare opportunity to track the daily movements of a Megamouth (specimen #6) off Dana Point, southern California. A 16-foot (5-metre) male specimen, it spent the daylight hours at depths of 400 to 550 feet (120 to 166 metres). At night, it rose to depths of 40 to 80 feet (12 to 25 metres) and returned to the depths before dawn. This individual Megamouth was tracked continuously for only 50.5 hours — two complete day-night cycles — but that was long enough to determine that its vertical movements were strongly correlated with ambient light levels. From the sum total of data collected at the time, the researchers concluded Megamouth is a vertical migrator that probably moves up and down as part of a complex community of mesopelagic animals known collectively as the Deep Scattering Layer (for its ability to scatter depth sounding echoes).

The

tracking data also revealed that Megamouth swims very slowly. The

telemetered individual moved southward at an average rate of 0.7 miles

(1.2 kilometres) per hour, but this speed was probably against a steady

current of 4 to 10 inches (10 to 25 centimetres) per second. Adjusting for

the opposing current, the shark’s actual speed relative to the water was

about 0.9 to 1.3 miles (1.5 to 2.1 kilometres) per hour. This is less than

half the average cruising speed recorded for large predatory sharks, such

as the White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) and Tiger Shark (Galeocerdo

cuvier), but only slightly slower than swimming speeds recorded for

other large planktivorous sharks, such as the Basking Shark (Cetorhinus

maximus) and Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus). But, at present, we

cannot be sure whether Megamouth’s slow cruising pace is due to its

filter-feeding mode of life, a strategy for saving energy in the

nutrient-poor mesopelagic, or simply an artifact of the physiological

sluggishness of muscles in the cold water characteristic of the deep-sea.

The

tracking data also revealed that Megamouth swims very slowly. The

telemetered individual moved southward at an average rate of 0.7 miles

(1.2 kilometres) per hour, but this speed was probably against a steady

current of 4 to 10 inches (10 to 25 centimetres) per second. Adjusting for

the opposing current, the shark’s actual speed relative to the water was

about 0.9 to 1.3 miles (1.5 to 2.1 kilometres) per hour. This is less than

half the average cruising speed recorded for large predatory sharks, such

as the White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) and Tiger Shark (Galeocerdo

cuvier), but only slightly slower than swimming speeds recorded for

other large planktivorous sharks, such as the Basking Shark (Cetorhinus

maximus) and Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus). But, at present, we

cannot be sure whether Megamouth’s slow cruising pace is due to its

filter-feeding mode of life, a strategy for saving energy in the

nutrient-poor mesopelagic, or simply an artifact of the physiological

sluggishness of muscles in the cold water characteristic of the deep-sea.

Little is known about the reproductive biology of Megamouth. Two male specimens captured off southern California in the late fall displayed evidence of recent or impending mating. The claspers of Megamouth #2 were oozing sperm and the clasper tips of Megamouth #6 were extensively abraded and bleeding, possibly indicating it had mated recently. The lower jaw of Megamouth #6 also showed abrasion, possibly due to a female grasping it during mating. Taken together, such circumstantial evidence suggests that Megamouth mating in the tropical eastern Pacific may occur during October and November.

The Megamouth Shark is occasionally observed at the surface during daylight hours. In October 1990 a pair of sea kayakers off Dana Point, California saw what was very probably a large Megamouth rise slowly and swim briefly along the surface. In August 1998, a Megamouth (#13) — estimated to be 16 feet (5 metres) long — was observed and photographed at the surface off Manado, Indonesia, apparently being attacked by a pod of three Sperm Whales (Physeter macrocephalus). Whether the whales were attempting to feed on the hapless shark or simply playing with it, as a cat does with a mouse, is not clear from the reports and photos. Vulnerability to predators may partially explain why Megamouth is so rarely seen at the surface during daylight hours. And it may also explain why such a large and otherwise conspicuous species was not ‘discovered’ until so very recently.

Most of our accumulated knowledge about Megamouth as a living creature has been deduced from dead or moribund specimens. At least three Megamouth specimens have been found stranded on shallow, sandy beaches, one in Western Australia (#3) and two in Japan (#4 and #5). It is hard to imagine a healthy deep-sea shark entering such shallow waters and stranding. Even the 16-foot (5-metre) male tracked off southern California (#6) was caught in a gillnet and kept overnight tethered on a short leash in a shallow, silty bay before it was outfitted with a telemetric device and released. Thus, a great deal of what we think we know about the Megamouth may be based on aberrant, ill, or moribund individuals.

But, as our exploration of the deep-sea continues into the 21st Century, opportunities to observe, film, and study the Megamouth Shark will undoubtedly increase, revealing new secrets and raising new questions about its mysterious life.

Megamouth Shark

Bibliography

More about: Megamouth |

Mega Joke |

Filter-feeding Elasmobranchs