The Evolution of Lamnoid Sharks

The lamnoids (order Lamniformes) include many of the most famous and instantly-recognizable of sharks. The Goblin Shark, Sandtiger, threshers, Megamouth, Basking, and the Great White are all members of this group. From the dim depths of prehistory, these sharks have left a rich fossil record.

As a group, lamnoids are characterized by heavily-built, solid teeth that have proven durable against the onslaught of erosion over geological time. As a result, their ancestors have left many beautiful and highly informative fossil teeth. In addition, the lamnoids have heavily calcified but fragile vertebral centra which are also sometimes preserved. Beyond these structural basics, only a few assorted fossilized bits and pieces survive - some of them squirreled away in private collections, where their true value remains hidden from paleontologists.

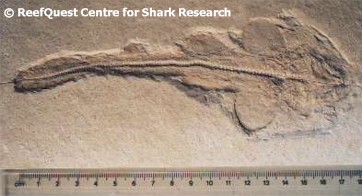

Recent work by David Ward

suggests that this 14-inch (90-centimetre), wobbegong-like fossil

species, known as Paleocarcharias stromeri

from the upper Jurassic (about 155 million years old) of what is now

Germany, may be the earliest known lamnoid. Specimen in the

collections of the British Museum of Natural History.

Recent work by David Ward

suggests that this 14-inch (90-centimetre), wobbegong-like fossil

species, known as Paleocarcharias stromeri

from the upper Jurassic (about 155 million years old) of what is now

Germany, may be the earliest known lamnoid. Specimen in the

collections of the British Museum of Natural History.

Curiously, very few lamnoids are known from articulated fossil remains. An important exception is Scapanorhynchus lewisii, which is known from well-preserved body fossils from early Cretaceous deposits (about 120 million years old) in Lebanon. Scapanorhynchus is believed to be a direct ancestor of the modern Goblin Shark (Mitsukurina owstoni), based on the many features they share such as a long, blade-like snout, striated, fang-like teeth, and a long tail with a weak lower lobe. Although the goblin shark can reach a length of 11 feet (3.4 metres), most specimens of Scapanorhynchus are much smaller, about two feet (65 centimetres) long. (A large, shallow water species known as S. texanus had 2-inch [5-centimetres] teeth, suggesting it grew as large as the extant goblin shark, but there is some contention whether these two sharks are actually related.) Scapanorhynchus is also known from numerous spike-like fossil teeth which are superficially similar to those of the Sandtiger (Carcharias) and have been confused with them, but differ in the presence of fine grooves on the inner surface near the base of the blade. These teeth are known from deposits representing most of the Cretaceous (about 120 to 65 million years old), in such widely scattered locations as Europe, Africa, southwestern Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Due to fortuitous finds such as these, it is seems likely that the goblin shark lineage diverged from the common ancestor of the lamnoids and became specialized relatively early in its evolutionary career.

Piecing Together the Fossil History of Lamnoids

Most of what we know about the evolution of lamnoid sharks comes from detailed studies of their fossilized teeth. Yet with only teeth to go on - no matter how beautifully preserved - it is extremely difficult to trace the evolutionary history of lamnoids. As a result, we often have more theories than we do specimens. Despite this paucity of data, the fossil record suggests two clear features of lamnoid evolution: these sharks underwent several massive bursts of adaptive radiation, followed by long periods of very slow and gradual diversification along separate lineages.

Fossil collector Gordon Hubbell has remarked that studying shark evolution is like watching a movie in slow motion. But at least with a movie, one has all the frames in order. In the shark fossil record, huge sections of the story are missing, distorted, or out-of-sequence and each specimen is more like a single frame from a very long movie. As such, the challenge facing shark paleontologists is more akin to figuring out a cohesive plot-line despite having only a few scattered and warped snapshots with which to work. The lamnoid sharks we see today are thus the products of a long, immensely convoluted history that is mostly hidden from human investigation.

Despite an abundant fossil record, how ancient

sharks are related to each other and to their modern descendants is far from

clear. This branching diagram is synthesized from the work of several

paleontologists. The diagram shows how many of the sharks discussed in this

chapter are interrelated. (Many forms are not included because there is too

little evidence to permit placing them confidently.) The branching sequence

is approximate only, showing roughly how various shark groups derived from

earlier forms. For example, some of the other lamnoids may well be - and

probably are - more closely related to the modern white shark than is

megalodon, but this is not shown here in the interests of making this

roadmap of shark history easier to read.

Despite an abundant fossil record, how ancient

sharks are related to each other and to their modern descendants is far from

clear. This branching diagram is synthesized from the work of several

paleontologists. The diagram shows how many of the sharks discussed in this

chapter are interrelated. (Many forms are not included because there is too

little evidence to permit placing them confidently.) The branching sequence

is approximate only, showing roughly how various shark groups derived from

earlier forms. For example, some of the other lamnoids may well be - and

probably are - more closely related to the modern white shark than is

megalodon, but this is not shown here in the interests of making this

roadmap of shark history easier to read.